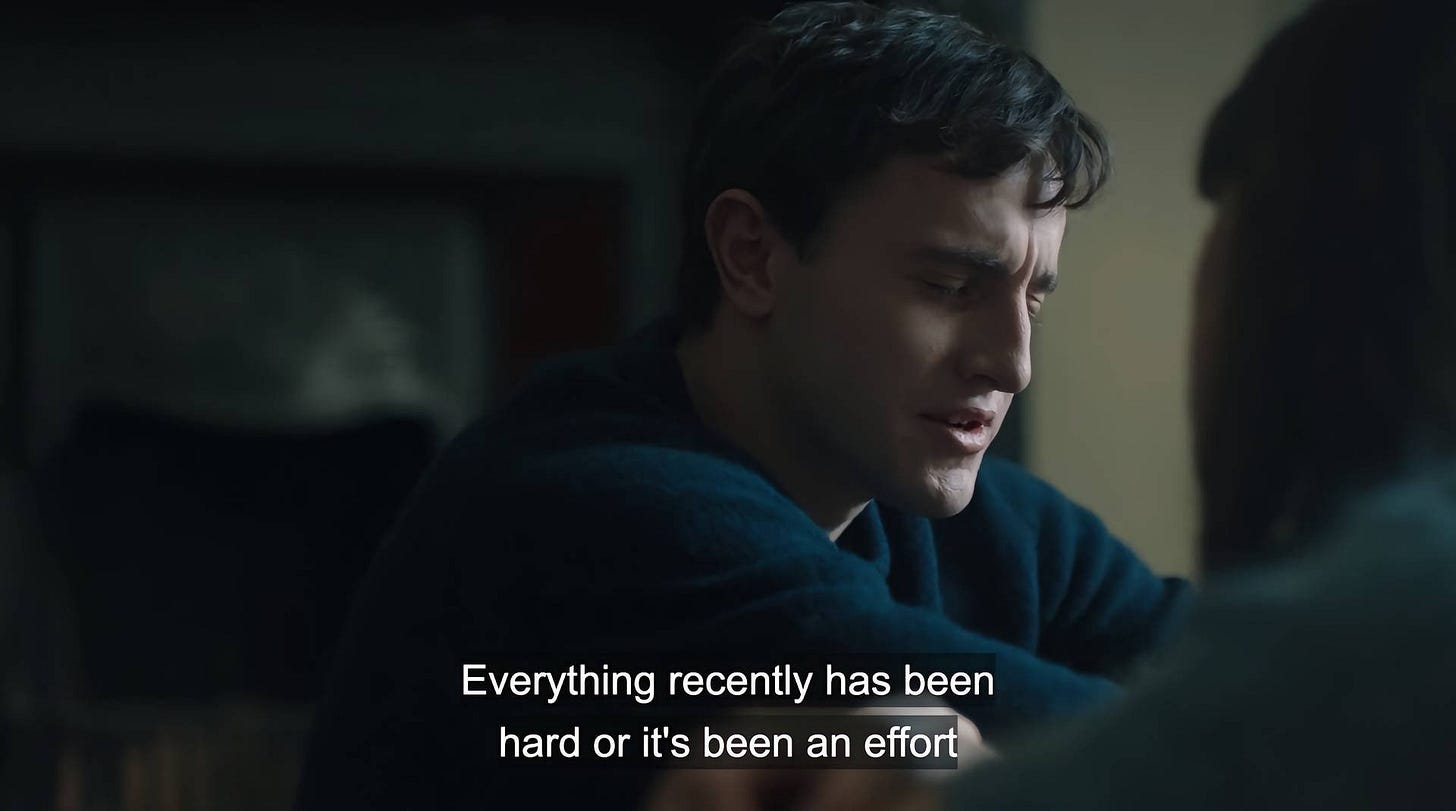

“I realised my life would be full of mundane physical suffering, and that there was nothing special about it. Suffering wouldn't make me special, and pretending not to suffer wouldn't make me special. Talking about it, or even writing about it, would not transform the suffering into something useful.” — Sally Rooney, Conversations With Friends

As writers, we often glamorize sadness. After all, it’s what we profit off of. I’ve said to many people that I’m not a good writer when I’m happy. In fact, I think a part of me yearns to self-sabotage anything that brings me joy. “It’ll make for a good story,” this part of me thinks. After all, what’s there to write about if you don’t feel a pit fester in the depths of your stomach, clawing its way to your brain as inspiration?

As we escape the dark and cold months of January and February (I don’t count December because the twinkling lights and the dreamy voice of Nat King Cole make it all too joyful), we reach the sunny and warmer months of spring. Spring has sprung, which means my inspiration will dwindle.

If I can’t sulk in the darkness of 5PM and write about someone from months ago, then what’s the point? There’s something about the stark, unforgiving winter that makes reflection easier. Something about early sunsets makes memories feel heavier, like the weight of nostalgia presses down harder in the cold, unrelenting to be forgotten. But when the days stretch longer and the world begins to thaw, the heaviness lifts, and I am restless, uninspired, and content. What good writer is content?

It seems as though the Pinterest-fied aesthetics of “sad girl” and “cool girl” have become synonymous. Society has glamorized the archetype of the starving, black-coffee-drinking, pseudo-intellectual woman who’s a wallflower, reading a book at crowded parties and holding a cigarette between her dainty, thin fingers. There’s something alluring about her beautifully tragic sadness. It’s why books and movies paint her as the one to watch. We are taught that to be interesting, to be worthy to be written about, we must first be tragic.

And I fell for it. When I was younger, I grew obsessed with perfecting this fictional role of the Cool Writer Girl. I ate less, thinking my hunger might make my thoughts sharper, more profound, more poetic. I drank black coffee, even when I hated the bitter taste, because it seemed like something a tortured writer would do. The very writers who idolize the words of Sylvia Plath and Virginia Woolf.

I ate granola bars instead of full meals, the pang in my stomach feeling like proof that I was disciplined, that I was the kind of girl who existed only on hunger and intellect. I walked through bookstores, wearing floral dresses and black eyeliner, with Joan Didion tucked under my arm. I imagined myself as the kind of person people watched and wondered about. I wanted to be fragile but brilliant, distant but alluring. I wanted to be a beautiful, untouchable enigma.

I wanted to be like the girls I’d read about and seen in movies, the ones with effortless beauty even with dark circles and messy hair. The ones who were lost in their own thoughts, scribbling furiously in their notebooks. I wanted to be mysterious and misunderstood. I lied about my favorite movies and singers because they weren’t poetic enough. I was too basic when I told the truth. I believed that if I wasn’t sad enough, if my life was too comfortable, too happy, too typical, then I had to find a way to make it hurt. I let good things slip away because who wants to read about stability? I let people go because longing and loss are poetic, and I wanted my life to be poetry.

Sally Rooney’s writing embodies the aesthetic I romanticized to the extent of replication. Her novels explain the quiet, intellectual melancholy of characters who are burdened by their own depth and emotions. Her protagonists exist in a haze of overanalysis and restrained emotion. Rooney’s characters don’t just feel pain, they thrive in it. They allow it to consume them, even when it’s destructive. Her novels reinforce the idea that melancholy is literary. Maybe that’s why I, and many other young writers, have felt drawn to the archetype of the unhinged, destructive, cool, detached woman. Literature has taught us that sadness is synonymous with significance. The more we suffer, the more we have to say.

Even now, I wonder if I still crave melancholy because it feels like home, because it feels like the birthplace of creativity. I wonder if I pull at the seams of my own happiness just to watch it unravel. Just so I have something to hang onto, something to write about when the seasons change and inspiration feels scarce.

Lately, I’ve been challenging that narrative. To unlearn the idea that misery is the prerequisite for excellence. To write from a place of presence rather than pain. Maybe I don’t have to be sad to be interesting. Maybe I don’t need to be tragic to be a writer. Maybe I can let the spring come without mourning the end of winter. Maybe happiness can be poetic, too.

All of my works are free, but if you’d like to support me and my writing, you can consider buying me a coffee :)

this perfectly articulated something i didn’t even realize i needed put into words.

It is past midnight and I just finished reading your post. I’ve asked this question so many times and seldom come up with a solution to this constant feeling of being stuck in melancholy. You’ve worded this ‘sucky’ feeling so perfectly. Thank you! ♥️